Production System in AI: Characteristics, Examples with Diagrams

Imagine machines solving complex problems by following clear, logical rules—much like expert systems that diagnose diseases or manage equipment repairs. Production systems in AI are exactly these rule-based frameworks that let computers reason in a step-by-step, explainable way. In technical terms, a production system uses a knowledge base of "if–then" rules, a working memory of facts, and an inference engine (control mechanism) to apply rules and draw conclusions.

This clear separation of knowledge and logic enables automated reasoning: for example, an AI medical system might use a rule such as "If a patient has fever, cough, and rash, then suggest testing for measles" to help guide a diagnosis. Production systems form the backbone of many agentic AI and expert systems, powering intelligent agents that autonomously apply domain expertise to achieve goals.

Key Characteristics of Production Systems

These systems have several core features that make them powerful for AI reasoning:

-

Rule-based knowledge representation: Expert knowledge is encoded as clear if–then rules. Each rule links conditions to actions or conclusions. This modular rule base ensures decisions follow expert logic in a transparent way.

-

Condition–action pairs (if–then rules): Rules explicitly match situations to responses. When the conditions of a rule are met, the rule "fires" and executes its action. This straightforward format (e.g. "IF X is true THEN do Y") makes reasoning traceable.

-

Working memory for facts: Production systems maintain a dynamic working memory (also called a global database) that holds all current facts about the problem. As the system reasons, it adds, updates, or removes facts in working memory, keeping track of the problem's state throughout the inference process.

-

Inference engine for matching rules: A control mechanism (the inference engine) continually scans working memory and the rule base, matching applicable rules and executing them. It decides which rule to apply and when, often using forward chaining (data-driven) or backward chaining (goal-driven) strategies. The engine's pattern-matching ensures that rules fire in a logical order until the goal is reached or no further rules apply.

These characteristics let production systems reason in a loop: match rules, fire one, update facts, and repeat, until a conclusion is drawn. For example, the system might match all rules whose conditions hold, select the highest-priority one, fire it to generate new facts, and continue. This cycle of matching–selecting–executing is at the heart of how production systems derive conclusions. Because the process manipulates symbolic facts and rules logically, the resulting decisions can be traced and explained step by step.

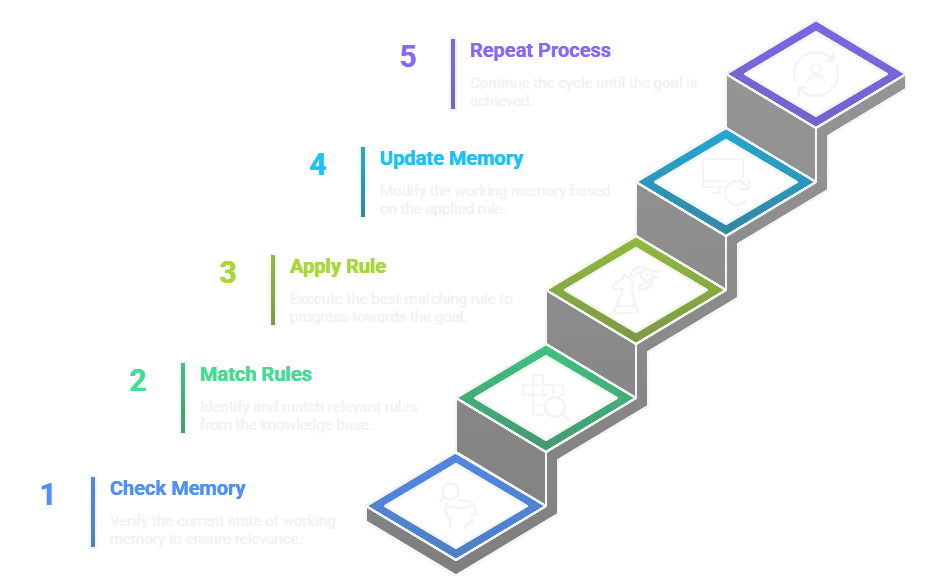

How Production Systems Work in AI

Production systems operate in a cyclic reasoning process. First, all known facts about the problem are loaded into working memory. The inference engine then matches these facts against the rule base: any rule whose condition is satisfied by the current facts becomes "triggered". If multiple rules match, a conflict resolution strategy (e.g. by rule specificity or priority) selects which rule to fire.

The chosen rule's action is then executed, which typically means updating the working memory (adding or modifying facts) or performing an action. The system loops back to match again with the updated facts, possibly triggering new rules. This match–fire–update cycle continues until the system reaches a goal or no more rules can fire.

Because each step is logically determined by the rules and facts, production systems maintain logical consistency: conclusions always follow from the activated premises. In practice, this means AI production systems can not only solve problems but also explain their reasoning path by showing which rules fired and how facts changed. In effect, a production system acts as the decision-making core of a rational AI agent, helping it choose actions to maximize goal achievement based on its knowledge.

Production System Types in AI

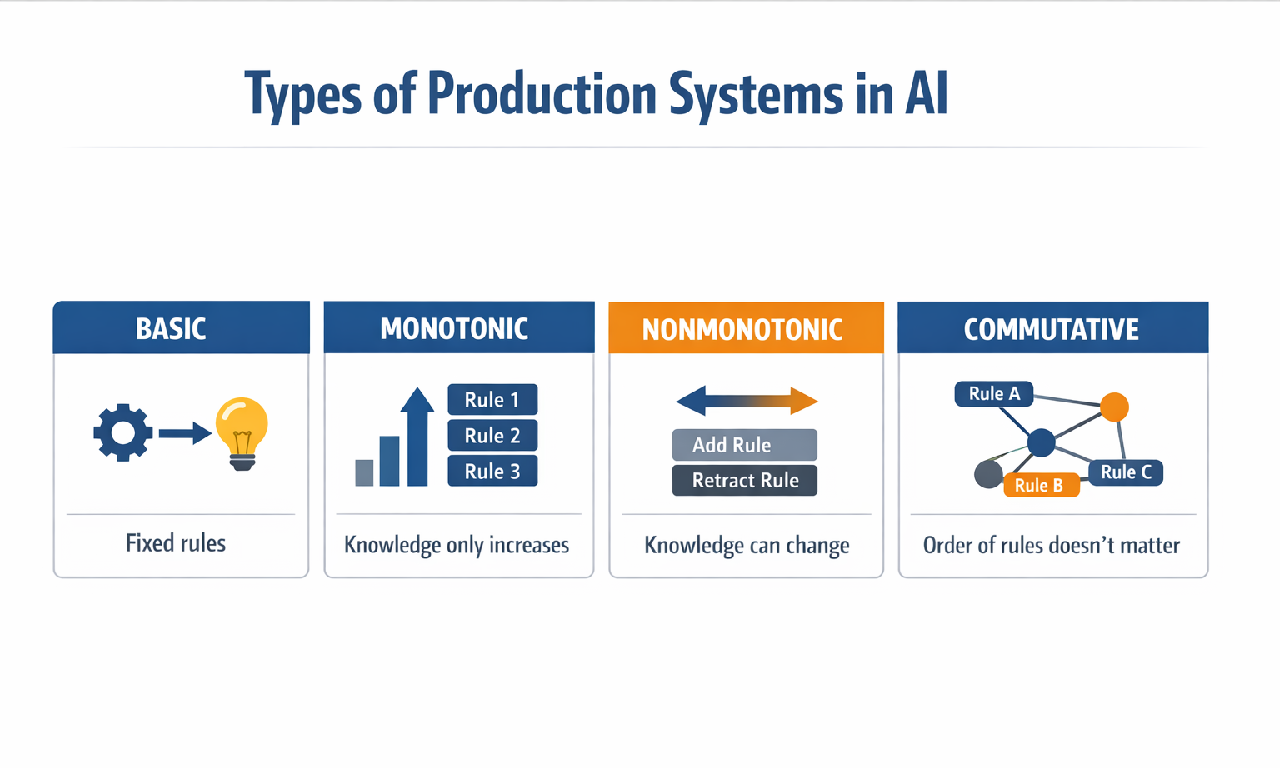

AI production systems can be categorized by how they apply rules and handle knowledge updates. Common types include:

Basic Production Systems

These use straightforward rule firing. Rules trigger as soon as their conditions match the current facts in working memory. The system simply applies the first matching rule in each cycle, without advanced control mechanisms. Such basic systems suit domains with clear, non-conflicting rules and relatively simple reasoning paths.

Monotonic Production Systems

In monotonic systems, once a fact is derived it remains true for the duration of reasoning. The system only adds new facts and never retracts or revises earlier ones. This ensures stable, consistent logic (no contradictions) and is ideal when information only accumulates. In monotonic reasoning, conclusions only add to the knowledge and never invalidate past inferences.

Nonmonotonic Production Systems

These systems allow beliefs to change with new information. A fact or rule can be retracted or revised when newer evidence arrives. Nonmonotonic reasoning is flexible and adaptive, suitable for dynamic domains where the initial rules might need updating. For example, a medical diagnosis system might initially suggest a disease (adding that fact) but later withdraw that conclusion when a new lab result contradicts it.

Commutative (and Partially Commutative) Systems

Some systems are designed so that the order of rule application does not affect the final outcome. In a commutative system, rules can fire in any sequence without changing the results, providing flexibility in execution. A partially commutative system allows some reordering of rules while still maintaining certain constraints. These types balance stability with adaptability by permitting multiple valid application orders.

Each type suits different needs: monotonic systems assume complete, unchanging information; nonmonotonic ones handle evolving or incomplete data; commutative designs ensure outcome consistency regardless of execution order.

Core Components of a Production System

A production system's architecture hinges on three main components working in concert:

1. Knowledge Base (Rule Base)

This is a repository of all the production rules (expert knowledge) relevant to the domain. Each rule is an IF–THEN statement (e.g. "IF fever AND cough THEN suggest flu"). The quality and completeness of this rule base determine how effectively the system can solve problems.

2. Working Memory (Fact Base)

This temporary storage holds all the facts currently known about the problem. It is dynamic: as rules fire, facts are added, changed, or removed here. Working memory represents the current state of the problem, and the inference engine continuously checks it against the rule base.

3. Inference Engine (Control Mechanism)

Often called the rule interpreter or engine, this component drives the reasoning process. It scans the working memory for facts that match rule conditions, decides which rule to fire (sometimes using forward or backward chaining), and then executes the rule's action (updating facts). Essentially, the inference engine links the knowledge base and working memory to produce conclusions.

These components form the classic production system loop. The knowledge base holds expert rules; the working memory keeps track of the current situation; the inference engine continuously applies rules to facts. Together, they enable the system to reason systematically through complex problems, much like a chain of logical implications.

Applications of Production Systems in AI

Production systems are widely used in domains that benefit from clear, expert-driven reasoning. Common applications include:

| Field | Example Applications |

|---|---|

| Healthcare | Diagnostic expert systems, treatment planning, drug interaction checks |

| Manufacturing | Quality control systems, process optimization, equipment troubleshooting |

| Finance | Credit scoring, fraud detection, automated risk assessment |

| Education | Intelligent tutoring systems, student assessment, personalized learning plans |

| Legal | Case law analysis, contract consistency checking, legal research support |

| Engineering | Design verification, fault diagnosis in systems, specification checking |

| Agriculture | Crop management advisories, pest detection, soil condition analysis |

| Expert systems (General) | Domain-specific consultation systems, decision support tools |

These are examples where encoding expert knowledge as rules helps automate decision-making. For instance, a production system in healthcare might systematically analyze symptoms (facts) against medical rules to suggest diagnoses, while a finance system might use rules to flag unusual transactions for fraud.

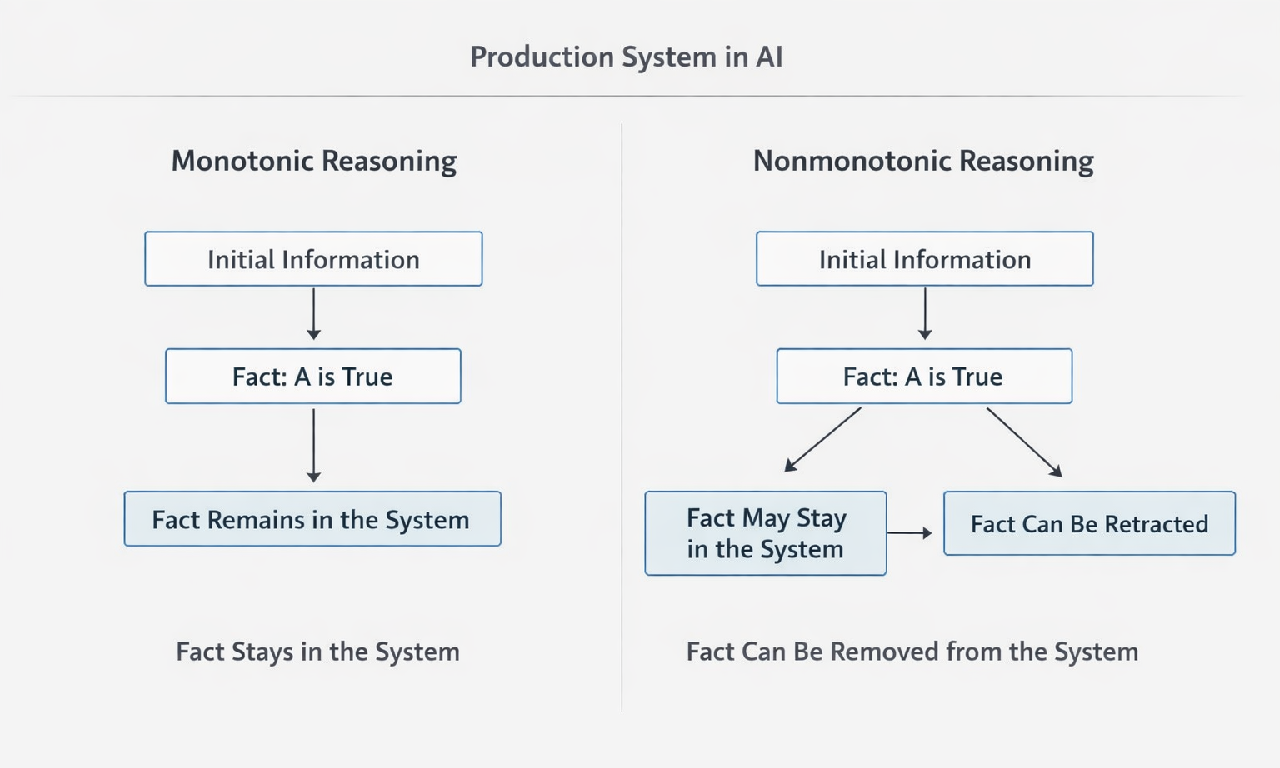

Monotonic vs Nonmonotonic Production Systems

Monotonic and nonmonotonic production systems differ fundamentally in how they treat knowledge over time.

In a monotonic production system, knowledge is cumulative. Once a fact or conclusion is derived through rule firing, it remains permanently true within the system. Adding new information can only increase the set of conclusions, never invalidate earlier ones. This makes monotonic systems predictable, efficient, and easier to implement. They work well in stable, well-defined environments where information is complete and does not change, such as configuration systems or rule-based validation engines.

A nonmonotonic production system, on the other hand, allows conclusions to be revised or withdrawn when new information becomes available. Facts are treated as provisional beliefs rather than permanent truths. When incoming data conflicts with existing assumptions, the system re-evaluates affected conclusions and updates its knowledge base accordingly. This behavior closely resembles human reasoning, where beliefs change as understanding improves.

Because conclusions may be retracted, nonmonotonic systems require additional mechanisms such as truth maintenance systems to track dependencies between facts and rules. These mechanisms increase system complexity and computational cost but enable reasoning under uncertainty, incomplete information, and changing conditions.

In practice, monotonic systems prioritize simplicity, speed, and logical consistency, while nonmonotonic systems prioritize adaptability and realism. The choice between them depends on the nature of the problem domain: static domains favor monotonic reasoning, whereas dynamic, real-world domains - such as diagnosis, planning, and intelligent agents - benefit significantly from nonmonotonic reasoning.

| Feature | Monotonic Systems | Nonmonotonic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Fact Management | Facts once derived stay permanently in the system. | Facts can be retracted or modified when new information conflicts. |

| Reasoning Direction | Typically forward-chaining from facts to conclusions. | Can use forward or backward chaining with belief revision. |

| Information Handling | Assumes information is complete and consistent. | Handles incomplete, uncertain, or changing information. |

| Logical Consistency | Maintains strict consistency; no contradictions arise over time. | May temporarily allow contradictions as beliefs are updated. |

| Suitable Domains | Best for stable domains where data only accumulates (e.g. configuration). | Suited to dynamic domains where conclusions may need revision (e.g. diagnosis). |

| Complexity | Generally simpler (no need to manage retractions). | More complex due to mechanisms needed for updating beliefs. |

| Truth Maintenance | No special maintenance needed, since beliefs only grow. | Requires a system to track dependencies and support belief revision. |

| Decision-making | Decisions are based on all accumulated, unchanged knowledge. | Decisions adapt to new evidence and changing circumstances. |

Conclusion

In summary, production systems in AI provide a transparent, rule-based framework for intelligent decision-making. By keeping rules (knowledge) separate from the reasoning process, they make complex problem-solving more understandable and manageable. These systems trace their roots back to classic expert systems, and continue to influence AI, especially where explainability and domain expertise are crucial.

Today, many enterprises combine production-system logic with machine learning to create hybrid AI solutions that are both powerful and interpretable. For example, GrowthJockey builds AI solutions that blend classic rule-based reasoning with modern ML, helping businesses scale AI revenue with trustworthy, explainable AI. If you need an AI solution you can understand and rely on, let's connect!

FAQs

1. What is a production system?

A production system is a rule-based AI framework for problem-solving. It uses a knowledge base of "if–then" rules, a working memory of facts, and an inference engine to match and apply rules. This lets the AI reason about situations step by step.

Q2. What are the different types of AI production systems?

Production systems can be classified by how they apply rules and handle knowledge. Common types include basic rule-based systems, monotonic systems (never retract facts), nonmonotonic systems (can revise beliefs), and commutative systems (rule order doesn't matter). These types vary in how they manage information and adapt to new evidence.

Q3. What are the four types of production systems?

A typical classification lists four types: Monotonic, Partially Commutative, Non-monotonic, and Commutative production systems. Monotonic systems only add facts, partially commutative systems allow some flexible rule ordering, non-monotonic systems can retract facts, and commutative systems permit any rule order without affecting outcomes.